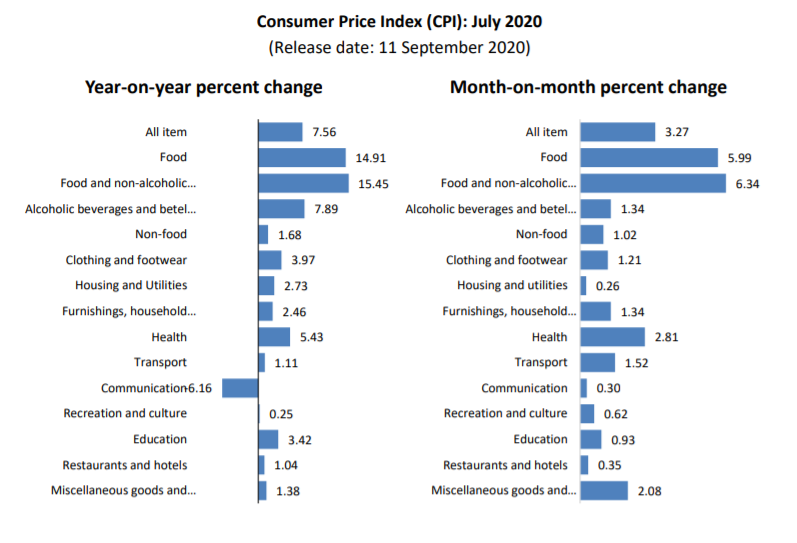

In its September 2020 report, the National Statistics Bureau (NSB) of Bhutan reported that the Consumer Price Index had increased by about 7.6% as of July 2020. Consequently, the Purchasing Power of Ngultrum had also depreciated by about 7% between July 2019 and July 2020. In other words, what used to benchmarked at NU. 100 in December 2012 is now worth only Nu. 67 in mid-2020. To sum up, living has just become a tad more expensive for the typical Bhutanese – as it has ever so slowly but steadily over the years. This brings to light the old tales among the dalesmen, “oh, back in the days, you were rich if you had a dime.” Forget dimes nowadays; the lakhs rarely count – even in the valley where supposedly, life should be more affordable and less impacted by the fluctuations in the global commodities market.

Perhaps what is revealing is that the high increase in CPI in July 2020 was mainly due to significant increases in the prices of food items. Firstly, to look at the brighter side of this dim picture is to give credit to our leaders, bureaucrats and recently, the agripreneurs, who have for decades invested time, money and authority into the policy of national food self-sufficiency. We have made some progress as a country, and it is sad we have not come as far as our lofty national objectives demand. But to be honest, we have to realize the stalemate we languish in when it comes to feeding ourselves. We have to realize that for decades, we have been getting on by clinging onto India Inc. for whatever we need as a nation – food, fuel, medicine, machine, money, labor, and … quite literally, everything else.

In this harangue, I want to focus on our food production system. Since we do not produce enough of what we eat, we have to import – mostly from India and Bangladesh but also from Thailand. And to be honest, we may blame multiple factors for the plight of our agriculture. Consider, for example, farm mechanization which is essential to cut costs of production and increase productivity. Bhutan’s rough terrain and unstable mountain pedology discourage mechanization at scale. Mountainside erosion and leaching easily drain the lands of their nutrients, thus decreasing yield. In such a context, farming in Bhutan is a Sisyphean endeavor in that farmers have to “feed” their fields with fertilizers and manures in return for disproportionately unsubstantial harvests, year in, year out. No wonder all farm parents advise their children to study and get government jobs in the towns and cities. Life is much easier when you are not a farmer.

But, there is little a country can do about its natural resource endowments. In fact, many other countries also struggle with undesirable terrains that impede easy agriculture. Thus, it is important that we consider the systemic factors that limit agricultural production in out country.

First lets look at the use and availability of agricultural land in the country. About 8% of Bhutan is arable out of which 3% is actively farmed and approximately 0.7% remains fallow for various reasons . This means 4.3% of Bhutan’s arable land remains un-cultivated. Why is that? I can go on about our humane tendencies to opt for the more comfortable ways of life – such as by getting a government job, or working in the cities to account for this. After all, such demographic changes directly take away from farming by draining our rural areas of farm labors. In addition, remaining on the farm after obtaining one’s schooling is seen as a sort of failure within some Bhutanese social milieu. Besides, one can also argue that given the lack of inherent economy of scale in Bhutanese farming, eking out a living as a farmer in Bhutan is difficult. This is especially true in the face of cheap imports from India. To add salt to the wound, pests and wild animals greatly dissuade some of our farmers in the east and south from continuing with farming. In a nutshell, the challenges keeping Bhutan from becoming a truly food sufficient nation are many and seemingly insurmountable.

But, I am more keen to ponder aloud our future opportunities, in a sense, obligations, as a nation when it comes to agriculture.

It is said that God made the world but the Dutch made the Netherlands. We can use this truism to posit the case for Bhutan to revamp and revolutionize its food production sector. And it is a pertinent case-study to inspire my argument on because Netherlands in the centuries before and Bhutan today face a similar dilemma: how does a nation house and transport its growing population on increasingly diminishing land while growing enough to feed them? For small Netherlands, it meant eking out land, square inch by square inch, from the sea by building dykes, water gates and wind-powered water pumps, AND centuries of maintaining these essential infrastructures. Consequently the Dutch have more than doubled their terrestrial acreage over the centuries. Where sea water once slosh over, they now graze their beautiful Holsteins, make mouth-watering cheeses, grow world-class flowers and produce enough food to have surpluses to export. All this while having a very high population density of 490 persons per square kilometer!

Fortunately for Bhutan, we do not have to fight the sea every day to keep our land habitable and arable. Nor do we have an overwhelming population density that eat away at good land. What we need, on the other hand, are a set of sound goal with a timeline vis-a-vis food production combined with a hurdle-free bureaucratic process to identify and nurture promising agricultural start-ups and projects. We have to open up access to arable government land for agriculture, strategically invest government subsidies in the folks, and where possible, play the trade well with export/import of priority crops such as grains and vegetables.

For one, our bureaucracy can do a better job. For example, in a recent notification, The National Land Commission (NLC) announced that it will no longer lease out government land for agriculture. It’s premise: there are 63,000 acres of registered land remaining fallow all across the country. In the proverbial words, they are beating the mattress because they are angry at the flea: རྩིགཔ་ཀི་ཤིག་ལུ་ཟ། ཀོམ་གདན་རྟས་ཐག་གིས་བརྡུང། but such policies will not help. Instead, the NLC can do well to study each application for land lease case by case, and take it from there. Institutional anger is rarely constructive but if they have legitimate reason to refuse a certain lease proposal based on a serious cost-benefit analysis, so be it.

Secondly, the process to lease land need not bee a labyrinthian get-this-get-that ordeal that it is today. As a small country of less than 800,000 citizens, we can leverage our small size as an advantage. Plus, we have a very big pool of civil servants in our nation who should be able to make all public engagements one-by-one; absolutely no need to silo each step of the bureaucratic processes in a different department or agency. And if we were to prioritize food production as a national goal, bureaucratic easing should come easier.

Thirdly, our planners and development officials can play strategic. Consider the dairy industry for instance. If, for whatever reasons, the government were to finance a milk processing unit for each and every valley, this would add up to a gargantuan sum, needless to say, very unnecessarily. Instead, they can help village cooperatives build seamless cold-chains, pool their milk and take it from there. Money salvaged there-off can be used to subsidize capital-intensive ventures for farmers – such as building modern and sanitary milk-stalls, pasture development and herd improvement. Quite literally, our livestock officials can single-mindedly make Bhutan dairy self-sufficient! Similar approaches in the crops and vegetables fields can do well to make us more food self-sufficient in the coming years.

Equally important, we need to re-evaluate our diet. Today, we say rice with ema datshi is the national dish of Bhutan. Actually, neither rice nor ema or datshi is uniquely “Bhutanese” per se. Rather, all are novel – rice originated in the warm terraces of South and South-east Asia. Chili came from the Andean highlands and spread over the globe with European colonization. Datshi may be the more Bhutanese part but in the past, we didn’t use to make datshi, and it was only with the advent of the Swiss in Bhutan that we did. Of course, we have been enjoying them for certain centuries which make them seem “Bhutanese.” This historical twist in our diet perspective is interesting, but it is more important to consider the questions it raises: What did we Bhutanese eat in the centuries before, then? Why do we grow so much potato when we do not consume it per se? Why are we so reluctant to fatten our sows, pluck our geese, and gut and gill our fish?

I am not arguing that all of a sudden, we should stop eating rice or not grow potato in Phobjikha. Rather, we can gravitate towards a diet-conscious nation where perhaps mashed potato, rice and bread feature equally frequently on our dinner tables. Then, we would not need to sell our hard-grown potato to buy starchy rice and fatty meats of dubious origins from god-knows-where. And perhaps, we should stop eating potato as curry along with rice. But then again, this habit is so steeped in our culture that it would be so difficult a challenge to surmount!

To be very honest, it is difficult for me to fathom how our planners, bureaucrats and economist can play the economics well to engender the goal of enhancing national food self-sufficiency. However, in a culture where the average highest aspiration is to get a well-paid government job, it is reasonably easy to deduce that there is room to play the numbers well. How can our financial institutions reduce interest on agricultural loans instead of doling out risk-free vehicle loans to civil servants? Which company or start-up is fomenting a promising revolution in food production in Bhutan? Which strategic sector of agriculture warrants the investment of that additional revenue from that new hydropower station? Can we draw up a smart national import-export policy for food produce that incentivizes food production inside Bhutan itself? Where do our farmers need more government-funded training? Can we plan and implement a national subsidy program for production of basic food produces? Which and how can our government agencies and employees help local agricultural entities and societies tap into grants and seed funding from international organizations and foundations?

I can not answer these questions by myself. And neither do I take for granted the government’s responsibility, ability and willingness to do all these. We have been spoon-fed by our leaders enough as it is. Besides, one may counter argue that Bhutan is not all agriculture and no education, health and etc… But consider this: Right now, more that 64% of Bhutanese live in the countryside, and with ever increasing unemployment, we are wont to see an increase in the medium-long run. If we cannot leverage this powerful demography as a strength, then I don’t know where we are headed as a nation…

At the same time, as we progress into the abyss of the 21st century, we know some things for sure: there will be a gradual but fundamental change in the way we produce and consume food. The only way to up our game is to be engaged in it – to be keen agriculturists with an imbued national consciousness for food production and food self-sufficiency. Along the way, we can pick-up new technologies, and adopt novel social and economic systems of food production to reflect the zeitgeist. However, the underlying goal will remains the old same: to produce enough food to realize food self sufficiency to a greater extent on the national level.

We have to deeply agree and adopt this national consciousness as a nation that we have to reform and revamp our food production because let not kid ourselves; AI, Robot Revolution, IoT, 5G, space travel, they are all going to come and have fundamental impacts on our society but at the end of the day, we will persevere with our existential need to eat – to eat good and eat well. And for that we cannot forever rely on a nation that is plagued by own set of problems, has to feeds its own population and may, for all reasons, leverage our steep reliance on its systems as a political tool to yield power. We must be responsible for every morsel of food that goes does our gullet.

And last but not the least also don’t forget:

0 Comments